What I learned from making a DNS client in Rust

Over the last few weeks I built my own DNS client. Mostly because I thought dig (the standard DNS client) was kinda clunky. Partly because I wanted to learn more about DNS. So here's how I built it, and how you can build your own too. It's a great weekend project, and I learned a lot from finishing it.

Why?

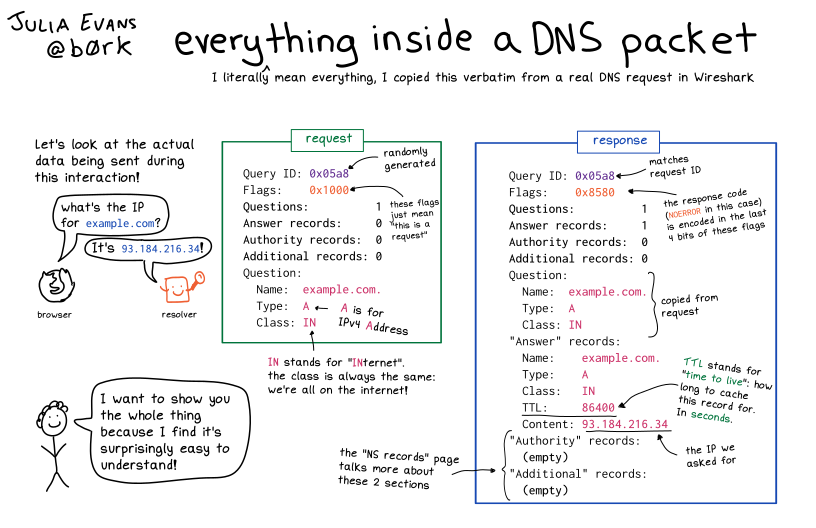

Julia Evans gave me the idea of making a DNS client. She's one of my favourite tech bloggers. Her blog always teaches me something, and often inspires me to go learn something new. She's also really good at summing up complex topics into really simple little cartoons, like this one:

When I read that comic, I was shocked -- the DNS query protocol is much simpler as I thought it would be. Also, I work at a company that is, uh, kind of a big player in the DNS world. I should probably understand it better.

The Plan

The other reason I wanted to make a DNS client is that I knew I could simplify every step using some great Rust crates. The plan:

-

Parse the CLI args using picoargs

It's not as powerful as clap, the standard Rust "enterprise-grade" CLI crate, and it requires some more boilerplate. But I don't really need advanced CLI features, and picoargs compiles way faster.

-

Serialize the DNS query using bitvec, an awesome general-purpose crate for reading or writing individual bits

I learned how to parse bitwise protocols with Nom when doing Advent of Code. I considered using deku instead but decided against it1.

-

Communicate with a DNS resolver with the stdlib UdpSocket type

I had no idea how this worked, but the Rust stdlib is really well-documented, so I was sure I could pick it up.

-

Parse the binary response with Nom

I learned how to parse bitwise protocols with Nom when doing Advent of Code. My previous blog post has a detailed guide to parsing DNS headers, using bit-level Nom for the one-bit flags and four-bit numbers.

-

Use plain old

println!to print the response to the user

How did I go?

It took around 800 lines of code, and I had it almost finished in a weekend. There was just one part of the spec I hadn't implemented: message compression (MC). Unfortunately that took me another weekend to do -- see below for more details.

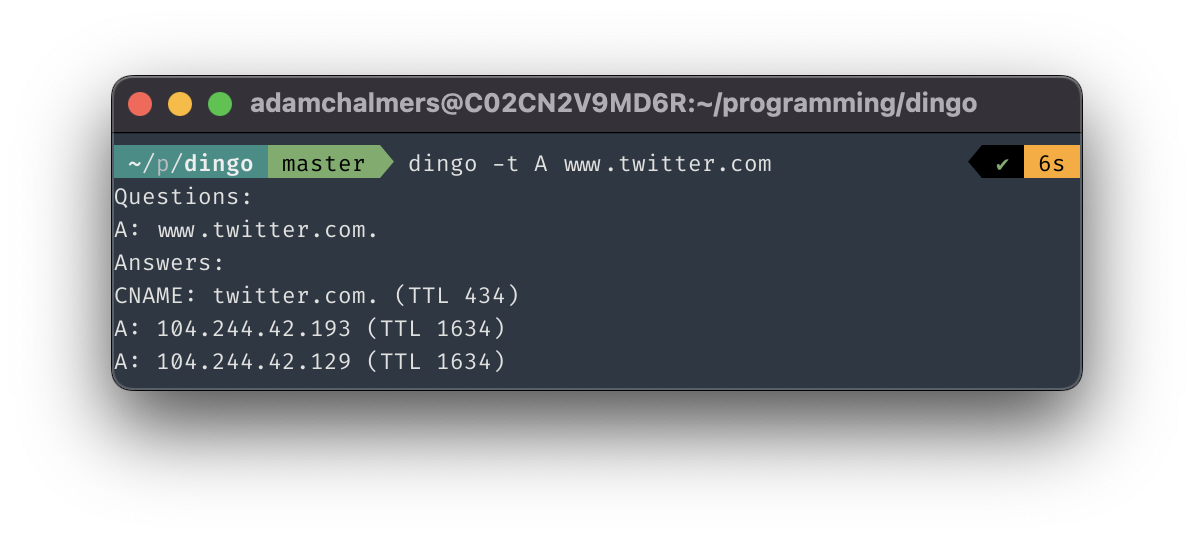

I named it Dingo because it sounded like dig, and it reminds me of Australia, my home. Anyway, it works!

It's pretty fast -- dig took 0.225 seconds on average to resolve A records for adamchalmers.com, and dingo took 0.028 seconds (both using 1.1.1.1 as the DNS resolver). Don't read too much into these numbers -- dig supports far more DNS features than my toy project. I'm only posting latency to prove my code isn't stupidly slow :)

You can install it or read the finished code on GitHub.

What did I learn?

Reading RFCs

I think a lot of programmers are intimidated by RFCs. At least, I'd like to think so, because I certainly am. Maybe all my peers are secretly RFC-loving little gremlins who get a heart-pounding high from reading plaintext ASCII diagrams... but they've never mentioned it.

RFC 1035 defines the DNS message protocol, so I had to read it very closely. This was my first time actually reading an RFC top-to-bottom, and I was surprised by how legible it was. I kept referring back to it, and I pasted key definitions and quotes from the RFC into source code comments, to help understand how all the pieces fit together. Maybe RFC 1035 is unusually good and the rest are actually all scary and incomprehensible. But I liked it.

(it's especially interesting reading this as a historical document, a primary source -- a lot has changed since the 1980s, and it's fascinating to learn what programmers back then were thinking, before the modern internet really existed)

Sockets

I've never been very comfortable with sockets. I tried reading Beej's guide to socket programming back in college, but I didn't really have the necessary OS, networking or C skills to make it through. I know about TCP and UDP, but I knew nothing about the lower-level abstractions that unify them.

This project was the first time I had to open a UDP socket -- in my regular programming, I've just relied on some networking library to handle that low level detail. So, I read the Rust docs for UDP sockets, which are remarkably clear. A lot of the methods on UdpSocket correspond directly to Linux syscalls. When I later went back and read Beej's socket guide properly, it was really easy. All these syscalls were familiar -- they're just Rust stdlib networking methods!

In fact, if I use dtruss (a MacOS tool for inspecting which syscalls your programs make2), I can see exactly what syscalls my program is using:

$ sudo dtruss dingo -t A www.twitter.com

# Skipping lots of syscalls just for starting a process on MacOS...

getentropy(0x7FF7BE8734E0, 0x20, 0x0) = 0 0 # Used by `rand` to generate a random DNS request ID

socket(0x2, 0x2, 0x0) = 3 0 # Create the UDP socket, aka "file descriptor 3"

ioctl(0x3, 0x20006601, 0x0) = 0 0 # Not sure, something about the UDP socket

setsockopt(0x3, 0xFFFF, 0x1022) = 0 0 # Set the options on the UDP socket

bind(0x3, 0x7FF7BE87346C, 0x10) = 0 0 # Bind the UDP socket to a local address

setsockopt(0x3, 0xFFFF, 0x1006) = 0 0 # Set more options, dunno why it needs more...

connect(0x3, 0x7FF7BE873584, 0x10) = 0 0 # Connect to the remote DNS resolver

sendto(0x3, 0x7FAE060041F0, 0x21) = 33 0 # Send the request to the remote DNS resolver

recvfrom(0x3, 0x7FAE060043F0, 0x200) = 79 0 # Get the response from the remote DNS resolver

close_nocancel(0x3) = 0 0 # Close the UDP socket

# Skipping lots of syscalls just for ending a process on MacOS

The syscalls connect, sendto and recvfrom are all from calling Rust methods UdpSocket::{connect, send_to, recv_from} -- they translate 1:1 into syscalls! That's really cool.

Bitvec

I really love Bitvec. It combines the usability and readability of Vec<bool> with the speed of using bit-twiddling tricks. It's the perfect example of Rust's no-compromises "ergonomics AND speed AND correctness" ideals.

The library exposes types for BitArray, BitVec and BitSlice. They mostly work the same, but I found two little confusing issues where they work differently. These were easily caught with unit tests, though, so I guess it's just a learning experience. The author hopes that after Rust ships more const generics features, they can release a Bitvec 2.0 where these types work the same.

Dig's weird output

I mentioned earlier that I hate using dig. It's got so many confusing fields and weird extraneous information. I just want to see what some hostname resolves to, and dig forces me to read all this extra info I don't care about.

$ dig adamchalmers.com

; <<>> DiG 9.10.6 <<>> adamchalmers.com

;; global options: +cmd

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 51459

;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 2, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 4096

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;adamchalmers.com. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

adamchalmers.com. 300 IN A 104.19.237.120

adamchalmers.com. 300 IN A 104.19.238.120

;; Query time: 80 msec

;; SERVER: 2600:1700:280:1f40::1#53(2600:1700:280:1f40::1)

;; WHEN: Sun Apr 10 17:48:43 CDT 2022

;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 77

But after implementing a DNS client, I actually know what all these mean! Like, "IN" doesn't mean the English word "in", it's short for "internet", because DNS technically supports many possible namespaces (it's just that we basically only ever use dig for internet DNS).

It's kind of cool reading dig output now because it's a reminder of how much I've learned. Oh yeah, I also learned that it's easy to make dig give you just the information you want:

$ dig +short adamchalmers.com

104.19.238.120

104.19.237.120

...if I'd known that back in January, I might never have started this project :)

I still fucking love enums

Enums are such a great way to express domain logic. Functional programmers have been talking about union types for decades now, and I'm glad they're finally appearing in other languages. It's hard to model domain logic in Go after using enums in Rust/Swift/Haskell.

Message compression (MC)

MC is a neat feature that DNS servers can use to reduce the size of their responses. Instead of repeating the same hostname multiple times in the response, MC replaces a hostname with a pointer back to a previously-cited hostname. The RFC actually explains it really well. MC helps servers fit their DNS responses into a single UDP packet, which is important because UDP is unreliable and doesn't care about truncated packets. MC requires looking back at the previously-parsed bytes, but Nom only lets you look ahead at remaining, unparsed bytes. It took several attempts before I could support MC in a nice, idiomatic Nom way (code), so that cost me another weekend of work.

Conclusion

This is one of my favourite projects I've done. My career goal for this year is to learn a lot more about Linux and networking. Writing dingo taught me a lot about one of the fundamental building blocks of the internet and how real operating systems handle it. If you're trying to learn more about low-level programming, a DNS client is a perfect challenge. It's got bitwise arithmetic, parsing, UDP networking, IP addresses and DNS hostnames. You'll learn a lot. In fact, after I wrote dingo, my friend Jesse Li wrote his own DNS client in Python. Clearly writing a DNS client is the hot new trend that you've got to get on. You should comment below if you try it :)

Footnotes

I tried deku, it's very nice! I like how it generates both serialization and deserialization methods using annotations on your struct's fields, so they never conflict, and you don't have to learn two separate libraries (bitvec and nom).

But I wanted practice explicitly using bitvec and getting comfortable with its API -- after all, I was only doing this project to learn things.

Also, deku uses serde and syn to power its (really helpful) serialization annotations. These crates are really powerful and can really reduce the boilerplate in your codebases. But they do add a fair bit of overhead to your build times. This isn't a problem at work, where my Rust projects are pretty large and already include serde/syn in the tree. But dingo didn't use either of them, so adding Deku would increase build time from 5 seconds to 15 seconds. I hope to use Deku in the future, but it didn't really fit for this particular project.

Syscalls are like functions the operating system defines, so the operating system can manage risky operations like I/O. Dtruss is a MacOS version of strace, a Linux tool. I learned how to use strace from Julia Evans' great strace comics which I highly recommend, I learned so much from it. Now when I write a program, I can spy on exactly what the compiled code is actually doing when it runs my functions.