Pin, Unpin, and why Rust needs them

- What are Futures?

- Trying and failing to use nested Futures

- Self-reference is unsafe

- Unpin and !Unpin

- Using Pin

- Using pin-project instead

- Summary

- References

Using async Rust libraries is usually easy. It's just like using normal Rust code, with a little async or .await here and there. But writing your own async libraries can be hard. The first time I tried this, I got really confused by arcane, esoteric syntax like T: ?Unpin and Pin<&mut Self>. I had never seen these types before, and I didn't understand what they were doing. Now that I understand them, I've written the explainer I wish I could have read back then. In this post, we're gonna learn

- What Futures are

- What self-referential types are

- Why they were unsafe

- How Pin/Unpin made them safe

- Using Pin/Unpin to write tricky nested futures

What are Futures?

A few years ago, I needed to write some code which would take some async function, run it and collect some metrics about it, e.g. how long it took to resolve. I wanted to write a type TimedWrapper that would work like this:

// Some async function, e.g. polling a URL with [https://docs.rs/reqwest]

// Remember, Rust functions do nothing until you .await them, so this isn't

// actually making a HTTP request yet.

let async_fn = reqwest::get("http://adamchalmers.com");

// Wrap the async function in my hypothetical wrapper.

let timed_async_fn = TimedWrapper::new(async_fn);

// Call the async function, which will send a HTTP request and time it.

let (resp, time) = timed_async_fn.await;

println!("Got a HTTP {} in {}ms", resp.unwrap().status(), time.as_millis())

I like this interface, it's simple and should be easy for the other programmers on my team to use. OK, let's implement it! I know that, under the hood, Rust's async functions are just regular functions that return a Future. The Future trait is pretty simple. It just means a type which:

- Can be polled

- When it's polled, it might return "Pending" or "Ready"

- If it's pending, you should poll it again later

- If it's ready, it responds with a value. We call this "resolving".

Here's a really easy example of implementing a Future. Let's make a Future that returns a random u16.

use std::{future::Future, pin::Pin, task::Context}

/// A future which returns a random number when it resolves.

#[derive(Default)]

struct RandFuture;

impl Future for RandFuture {

// Every future has to specify what type of value it returns when it resolves.

// This particular future will return a u16.

type Output = u16;

// The `Future` trait has only one method, named "poll".

fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, _cx: &mut Context) -> Poll<Self::Output> {

Poll::ready(rand::random())

}

}

Not too hard! I think we're ready to implement TimedWrapper.

Trying and failing to use nested Futures

Let's start by defining the type.

pub struct TimedWrapper<Fut: Future> {

start: Option<Instant>,

future: Fut,

}

OK, so a TimedWrapper is generic over a type Fut, which must be a Future. And it will store a future of that type as a field. It'll also have a start field which will record when it first was first polled. Let's write a constructor:

impl<Fut: Future> TimedWrapper<Fut> {

pub fn new(future: Fut) -> Self {

Self { future, start: None }

}

}

Nothing too complicated here. The new function takes a future and wraps it in the TimedWrapper. Of course, we have to set start to None, because it hasn't been polled yet. So, let's implement the poll method, which is the only thing we need to implement Future and make it .awaitable.

impl<Fut: Future> Future for TimedWrapper<Fut> {

// This future will output a pair of values:

// 1. The value from the inner future

// 2. How long it took for the inner future to resolve

type Output = (Fut::Output, Duration);

fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context) -> Poll<Self::Output> {

// Call the inner poll, measuring how long it took.

let start = self.start.get_or_insert_with(Instant::now);

let inner_poll = self.future.poll(cx);

let elapsed = self.elapsed();

match inner_poll {

// The inner future needs more time, so this future needs more time too

Poll::Pending => Poll::Pending,

// Success!

Poll::Ready(output) => Poll::Ready((output, elapsed)),

}

}

}

OK, that wasn't too hard. There's just one problem: this doesn't work.

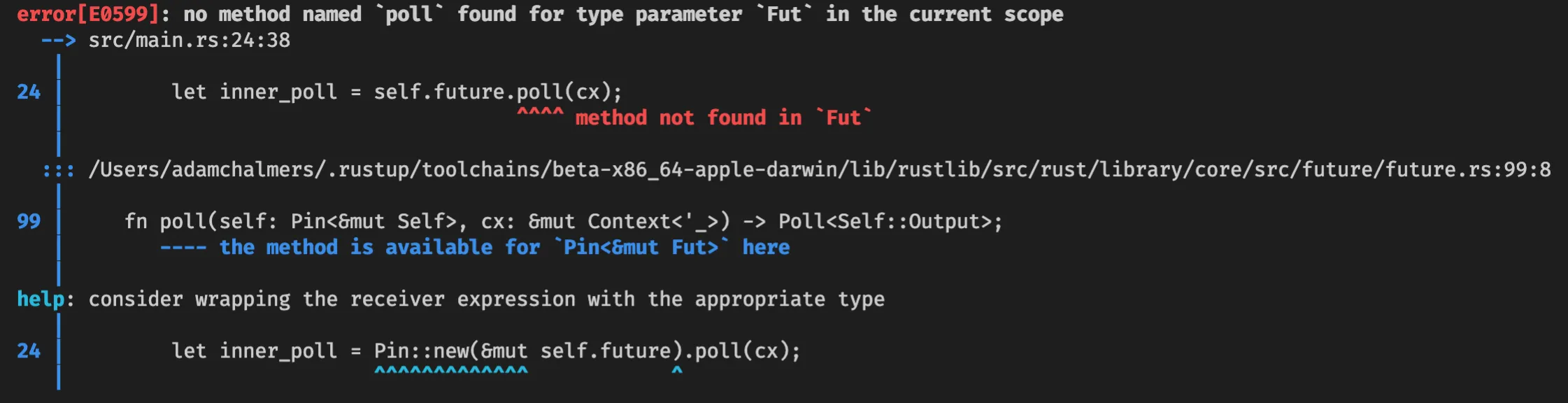

So, the Rust compiler reports an error on self.future.poll(cx), which is "no method named poll found for type parameter Fut in the current scope". This is confusing, because we know Fut is a Future, so surely it has a poll method? OK, but Rust continues: Fut doesn't have a poll method, but Pin<&mut Fut> has one. What is this weird type?

Well, we know that methods have a "receiver", which is some way it can access self. The receiver might be self, &self or &mut self, which mean "take ownership of self," "borrow self," and "mutably borrow self" respectively. So this is just a new, unfamiliar kind of receiver. Rust is complaining because we have Fut and we really need a Pin<&mut Fut>. At this point I have two questions:

- What is

Pin? - If I have a

Tvalue, how do I get aPin<&mut T>?

The rest of this post is going to be answering those questions. I'll explain some problems in Rust that could lead to unsafe code, and why Pin safely solves them.

Self-reference is unsafe

Pin exists to solve a very specific problem: self-referential datatypes, i.e. data structures which have pointers into themselves. For example, a binary search tree might have self-referential pointers, which point to other nodes in the same struct.

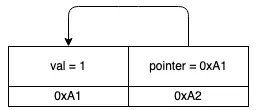

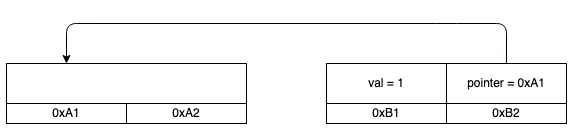

Self-referential types can be really useful, but they're also hard to make memory-safe. To see why, let's use this example type with two fields, an i32 called val and a pointer to an i32 called pointer.

So far, everything is OK. The pointer field points to the val field in memory address A, which contains a valid i32. All the pointers are valid, i.e. they point to memory that does indeed encode a value of the right type (in this case, an i32). But the Rust compiler often moves values around in memory. For example, if we pass this struct into another function, it might get moved to a different memory address. Or we might Box it and put it on the heap. Or if this struct was in a Vec<MyStruct>, and we pushed more values in, the Vec might outgrow its capacity and need to move its elements into a new, larger buffer.

When we move it, the struct's fields change their address, but not their value. So the pointer field is still pointing at address A, but address A now doesn't have a valid i32. The data that was there was moved to address B, and some other value might have been written there instead! So now the pointer is invalid. This is bad -- at best, invalid pointers cause crashes, at worst they cause hackable vulnerabilities. We only want to allow memory-unsafe behaviour in unsafe blocks, and we should be very careful to document this type and tell users to update the pointers after moves.

Unpin and !Unpin

To recap, all Rust types fall into two categories.

- Types that are safe to move around in memory. This is the default, the norm. For example, this includes primitives like numbers, strings, bools, as well as structs or enums entirely made of them. Most types fall into this category!

- Self-referential types, which are not safe to move around in memory. These are pretty rare. An example is the intrusive linked list inside some Tokio internals. Another example is most types which implement Future and also borrow data, for reasons explained in the Rust async book.

Types in category (1) are totally safe to move around in memory. You won't invalidate any pointers by moving them around. But if you move a type in (2), then you invalidate pointers and can get undefined behaviour, as we saw before. In earlier versions of Rust, you had to be really careful using these types to not move them, or if you moved them, to use unsafe and update all the pointers. But since Rust 1.33, the compiler can automatically figure out which category any type is in, and make sure you only use it safely.

Any type in (1) implements a special auto trait called Unpin. Weird name, but its meaning will become clear soon. Again, most "normal" types implement Unpin, and because it's an auto trait (like Send or Sync or Sized1), so you don't have to worry about implementing it yourself. If you're unsure if a type can be safely moved, just check it on docs.rs and see if it impls Unpin!

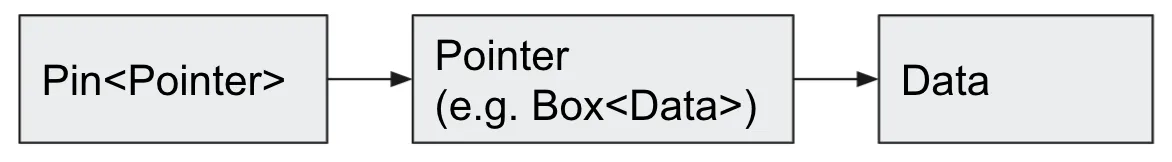

Types in (2) are creatively named !Unpin (the ! in a trait means "does not implement"). To use these types safely, we can't use regular pointers for self-reference. Instead, we use special pointers that "pin" their values into place, ensuring they can't be moved. This is exactly what the Pin type does.

Pin wraps a pointer and stops its value from moving. The only exception is if the value impls Unpin -- then we know it's safe to move. Voila! Now we can write self-referential structs safely! This is really important, because as discussed above, many Futures are self-referential, and we need them for async/await.

Using Pin

So now we understand why Pin exists, and why our Future poll method has a pinned &mut self to self instead of a regular &mut self. So let's get back to the problem we had before: I need a pinned reference to the inner future. More generally: given a pinned struct, how do we access its fields?

The solution is to write helper functions which give you references to the fields. These references might be normal Rust references like &mut, or they might also be pinned. You can choose whichever one you need. This is called projection: if you have a pinned struct, you can write a projection method that gives you access to all its fields.

Projecting is really just getting data into and out of Pins. For example, we get the start: Option<Duration> field from the Pin<&mut self>, and we need to put the future: Fut into a Pin so we can call its poll method). If you read the Pin methods you'll see this is always safe if it points to an Unpin value, but requires unsafe otherwise.

// Putting data into Pin

pub fn new <P: Deref<Target:Unpin>>(pointer: P) -> Pin<P>;

pub unsafe fn new_unchecked<P> (pointer: P) -> Pin<P>;

// Getting data from Pin

pub fn into_inner <P: Deref<Target: Unpin>>(pin: Pin<P>) -> P;

pub unsafe fn into_inner_unchecked<P> (pin: Pin<P>) -> P;

I know unsafe can be a bit scary, but it's OK to write unsafe code! I think of unsafe as the compiler saying "hey, I can't tell if this code follows the rules here, so I'm going to rely on you to check for me." The Rust compiler does so much work for us, it's only fair that we do some of the work every now and then. If you want to learn how to write your own projection methods, I can highly recommend this fasterthanli.me blog post on the topic. But we're going to take a little shortcut.

Using pin-project instead

So, OK, look, it's time for a confession: I don't like using unsafe. I know I just explained why it's OK, but still, given the option,

I didn't start writing Rust because I wanted to carefully think about the consequences of my actions, damnit, I just want to go fast and not break things. Luckily, someone sympathized with me and made a crate which generates totally safe projections! It's called pin-project and it's awesome. All we need to do is change our definition:

#[pin_project::pin_project] // This generates a `project` method

pub struct TimedWrapper<Fut: Future> {

// For each field, we need to choose whether `project` returns an

// unpinned (&mut T) or pinned (Pin<&mut T>) reference to the field.

// By default, it assumes unpinned:

start: Option<Instant>,

// Opt into pinned references with this attribute:

#[pin]

future: Fut,

}

For each field, you have to choose whether its projection should be pinned or not. By default, you should use a normal reference, just because they're easier and simpler. But if you know you need a pinned reference -- for example, because you want to call .poll(), whose receiver is Pin<&mut Self> -- then you can do that with #[pin].

Now we can finally poll the inner future!

fn poll(self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context) -> Poll<Self::Output> {

// This returns a type with all the same fields, with all the same types,

// except that the fields defined with #[pin] will be pinned.

let mut this = self.project();

// Call the inner poll, measuring how long it took.

let start = this.start.get_or_insert_with(Instant::now);

let inner_poll = this.future.as_mut().poll(cx);

let elapsed = start.elapsed();

match inner_poll {

// The inner future needs more time, so this future needs more time too

Poll::Pending => Poll::Pending,

// Success!

Poll::Ready(output) => Poll::Ready((output, elapsed)),

}

}

Finally, our goal is complete -- and we did it all without any unsafe code.

Summary

If a Rust type has self-referential pointers, it can't be moved safely. After all, moving doesn't update the pointers, so they'll still be pointing at the old memory address, so they're now invalid. Rust can automatically tell which types are safe to move (and will auto impl the Unpin trait for them). If you have a Pin-ned pointer to some data, Rust can guarantee that nothing unsafe will happen (if it's safe to move, you can move it, if it's unsafe to move, then you can't). This is important because many Future types are self-referential, so we need Pin to safely poll a Future. You probably won't have to poll a future yourself (just use async/await instead), but if you do, use the pin-project crate to simplify things.

I hope this helped -- if you have any questions, please ask me on Twitter. And if you want to get paid to talk to me about Rust and networking protocols, my team at Cloudflare is hiring, so get in touch at [email protected] (apply ROT13).

References

- Complete TimedWrapper example code on GitHub

- This post is based on a presentation I gave at a Rust Bay Area meetup a few weeks ago. My talk starts around 40 minutes in.

- The std::pin docs have a pretty good explanation of Pin's details.

- The Rust async book explains why Futures often need self-referential pointers.

- Comprehensive article on how pin projection actually works by @fasterthanlime

- Great article explaining when and how Rust moves values to different memory addresses, by @HashRust

Thanks to Nick Vollmar for feedback and to Shepmaster for helping me use pin-project when I first needed to write a nested Future

Footnotes

OK technically Sized isn't an auto trait, but it basically is, because the compiler has a special case for it. See this discussion for why!