Solving common problems with Kubernetes

- Introduction: why use k8s?

-

Solving problems with Kubernetes

- Problem: I want to run a container

- Problem: what is my pod doing?

- Problem: I want my container to restart when it crashes.

- Problem: My container should never have downtime, even when it crashes.

- Problem: My container can't handle the amount of traffic it's receiving.

- Problem: I need to deploy a new version of my backend, without causing downtime

- Problem: I need to route traffic to all pods in a deployment

- Problem: Load balancing across Pods

- Problem: I want to accept traffic from outside the cluster

- Problem: I want to limit networking within the cluster

- Problem: I want to use HTTP/S outside the cluster and HTTP inside the cluster

- Problem: I want to get metrics about my service

- Problem: I want isolation from other projects using the same cluster

- Conclusion

I first learned Kubernetes ("k8s" for short) in 2018, when my manager sat me down and said "Cloudflare is migrating to Kubernetes, and you're handling our team's migration." This was slightly terrifying to me, because I was a good programmer and a mediocre engineer. I knew how to write code, but I didn't know how to deploy it, or monitor it in production. My computer science degree had taught me all about algorithms, data structures, type systems and operating systems. It had not taught me about containers, or ElasticSearch, or Kubernetes. I don't think I even wrote a single YAML file in my entire degree. I was scared of ops. I was terrified of Kubernetes.

Eventually I made it through and migrated all the Cloudflare Tunnel infrastructure from Marathon to Kubernetes. I didn't enjoy it, and I was way over my deadline, but I did learn a lot. Now it's 2022, and I'm leading a small team of engineers, some of whom have never used Kubernetes before. So I've found myself explaining Kubernetes to them. They seemed to find it helpful, so I thought I'd write it down and share it with the rest of you.

This article is aimed at engineers who need to deploy their code using Kubernetes, but have no idea what Kubernetes is or how it works. I'm going to tell you a story about a junior engineer. We're going to follow this engineer as they build a high-quality service, and when they run into problems, we'll see how Kubernetes can help solve them. Hopefully this will get you comfortable building your own services in k8s!

Introduction: why use k8s?

What problem is k8s even trying to solve? Why do we need another new complicated software system, with its own weird proper nouns and YAML schemas and certification process? I'll answer this, but before I do, we need to take a quick step back and rewind to 2013, where the software industry first became obsessed with:

Containers

Say you want to deploy two Python servers. One of them needs Python 3.4 and the other needs Python 3.5. How do you deploy them on the same machine? You can hack a shell script together, maybe use Python-specific tools like venv. Fine, that works. But it doesn't scale very well, when you start deploying dozens of Python services, especially because you get similar problems with Node or Ruby or all the other languages you're using.

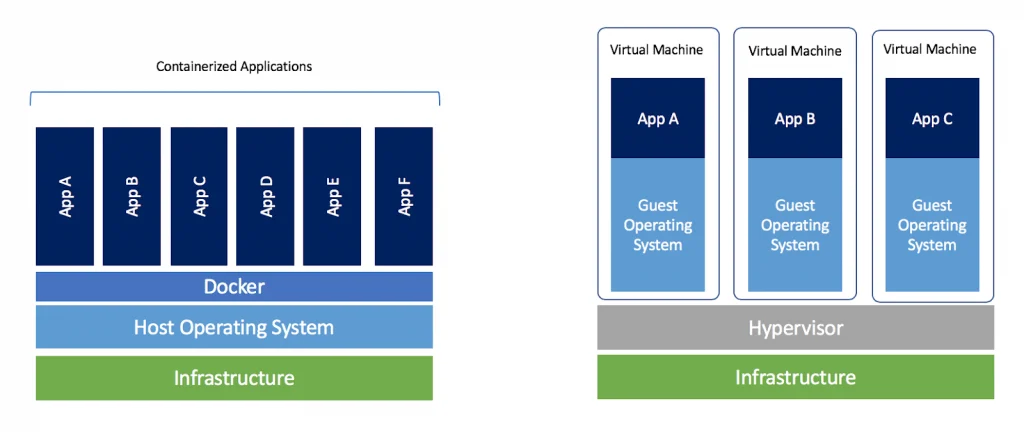

So instead, you run each Python server in its own container. A container, like a Virtual Machine, lets your service act like it's the only service on this machine. It gets its own clean filesystem, and now you don't have to worry about clashes with other dependencies. Great!

The big advantage containers have over VMs is that they're really lightweight. You can run way more containers on a single machine than VMs. Why? Because each VM has to install its own OS, but containers can share the same underlying OS.

For more beginner-level intro to containers, read this.

You can now deploy all your services on the same machine, each with their own container, in complete isolation. There's no way they can interfere with each other. This is awesome until you realize your services actually do need to talk to each other sometimes. Turns out letting processes message each other is a pretty common thing and critical to your job. Your company probably uses a service-oriented architecture, or maybe microservices, but either way, there's probably several services that need to communicate to handle requests. For example, frontends, backends, load balancers, session management, auth, user entitlements, writing logs, and billing might all be separate services that need to communicate. If you containerize all these services, you make it impossible for them to coordinate -- by design.

Container orchestration

Damnit! We have a problem. Using containers, we built each service a perfect little isolated cell, so they can't communicate. But we did our job too perfectly, we actually do need them to communicate. But only in specific ways that you, the programmer, choose. We don't want to go back to the pre-container days where all programs shared everything -- we saw how much of a mess that creates.

The other problem you'll face is which containers should be running in the first place. Let's say your company has a Continuous Integration system which runs every time you merge a PR to master. You can use it to create a new container image for every commit to your codebase, packaging up your code and all its dependencies (e.g. libraries to link, or a particular version of Python). Now if your commit changes the code's dependencies, that commit's container image will have the right combination of code and dependencies. But now you've got all these hundreds or thousands of containers. How do you tell your servers which containers to run?

We solve this with a container orchestration program, which selectively enables some containers and grants them some resources, including "communication with other containers". The phrase "container orchestration" is a metaphor for an orchestra. Imagine if no musicians in the orchestra could hear each other. They'd play at different speeds, the trumpets would drown out the oboes, every violinist would assume they were the soloist, and none of them would play the harmony parts. It would be chaos. To make this mess of isolated musicians into an orchestra, you need structure and to enforce structure, you need a good conductor.

A container orchestration program lets you:

- Choose which containers should run

- How many copies of each container should run

- Which containers are allowed to share resources, like volumes or directories or files or networks

- Choose which containers can access the same ports and hosts, to network with each other

Containers solve the problem of "how do I stop these services interfering with each other". Container orchestration solves "how do I let these services work together". They also solve "which services should be running".

There are many different competing orchestration tools. You might have used Docker Compose, it's simple and it's built into Docker, the most popular container engine1. If you only need to run your containers on one physical machine, then Docker Compose is the orchestrator I'd suggest. But of course, today's software companies never deploy software to just one machine. Firstly, that single machine probably can't handle all your traffic. Secondly, even if it could, it would be a single point of failure -- if that machine goes down, your services become unavailable, and your customers can't place orders, and you lose money. So, real-world engineers need to orchestrate containers across many different physical servers.

When I joined Cloudflare, we used Apache Marathon for this, but we were rapidly migrating to Kubernetes. This led to one big question:

Why kubernetes?

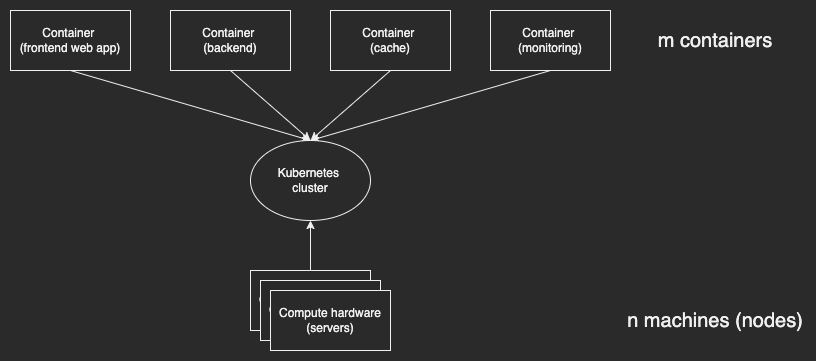

Kubernetes exists to solve one problem: how do I run m containers across n servers?

Its solution is a cluster. A Kubernetes cluster is an abstraction. It's a big abstract virtual computer, with its own virtual IP stack, networks, disk, RAM and CPU. It lets you deploy containers as if you were deploying them on one machine that didn't run anything else. Clusters abstract over the various physical machines that run the cluster.

The cluster runs on your n servers. A server which is part of a Kubernetes cluster is called a node.

A good abstraction should hide details from you, but let you access those details if you really need to. Generally your containers don't know and don't care which node they're running on -- the abstraction of the cluster is good enough. But if you really need to, you can query and inspect the various nodes that make up the cluster.

Your company might have one Kubernetes cluster, or it might have many. At a certain level of scale, you might want multiple clusters -- maybe one cluster for production and one for staging, or one cluster in each of America, Europe and Asia. Your SRE or platform team will probably let you know which cluster to deploy to.

So, why use Kubernetes?

- You want to use containers, to deploy your services in isolation from each other

- You want to use a container orchestrator, to manage deployment of your containers and sharing resources between them

- If you're running on one machine, just use Docker Compose

- If you're running on many machines, which might come up and down, and need to schedule your containers across them, use Kubernetes.

Solving problems with Kubernetes

I'm going to walk you through the various problems that a typical software engineer would encounter when trying to run a new, scalable, resilient, highly-available web service. We'll look at the standard solutions for these problems, and how you solve them in Kubernetes. By the time you finish this, you'll hopefully know enough to k8s to be productive.

By the way, whenever I Capitalize a Word making it into a Proper Noun, that's because it's got a particular meaning in the k8s world, e.g. Pod or Service. I'll link to the docs for that concept the first time I use it.

Problem: I want to run a container

Let's start simple. You've been working on a project code-named kangaroo and it's ready for deployment. So you build a container image to run it: kangaroo-backend. Your workplace runs their services in a Kubernetes cluster, so you need to deploy this container into the cluster. How? You need to define a Kubernetes Pod. A pod is a set of one or more containers (usually just one container, though2). Pods are the minimum unit of deployment in Kubernetes. It's the simplest, smallest thing you can deploy in k8s. So let's define a Pod that runs our container, like this:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: kangaroo-backend

spec:

containers:

- name: kangaroo-backend

image: kangaroo-backend:1.14.2

ports:

- containerPort: 80

This YAML defines a new k8s resource, which you can deploy to your cluster. All resources, regardless of what you're deploying, have four properties:

- apiVersion: Which version of the k8s resource definition to use. Resource definitions (like Pod) have a version so the Kubernetes committee can change the definition later, without breaking everyone using the old version. When you write APIs, you probably include a "v1" at the start just in case you need to make a backwards-incompatible change later. Well, the Kubernetes committee do the same thing.

- kind: All resources are of a particular kind -- in this case, a Pod.

- metadata: Key-value pairs that you can use to query and organize the resources in your cluster

- spec: The details of what you're deploying. Every kind has a spec. E.g. the Pod kind of resource has to have a

containerskey with an array of containers, each of which has animage.

We're deploying a pod, which is one or more containers (usually just one), so we've set kind: Pod and have to provide the right spec. Here our spec says we're running one container, image kangaroo-backend:1.14.2. We also let Kubernetes know that the container will be listening on port 80.

OK! If we save this as pod.yaml we can deploy it by running kubectl apply -f pod.yaml. Congratulations, you just deployed a container to your k8s cluster.

Problem: what is my pod doing?

So you deployed a pod. OK. Is it working? Is it doing what you expect it to do?

You can use kubectl to inspect your pod. Firstly, I suggest aliasing kubectl to k in your terminal, because you'll be using it a lot. You can run k get pods to see a list of pods you've deployed, k describe pod <ID> to see more information about that pod. If your pod logs to stdout/stderr, use k logs <ID> to see the pod's logs. If you're really unsure about a pod, you can SSH into it by running k exec <pod ID> -it -- /bin/bash. More tips like this at the Kubernetes Debug Running Pods page.

Problem: I want my container to restart when it crashes.

Project Kangaroo is going well, but every few days it crashes. It's an important service, so it should always be restarted when it crashes. If this was a normal Linux process on a normal Linux server, you could use a shell script to restart it, or maybe systemd. But how do you ensure your k8s pod gets automatically restarted?

Here's where k8s' big strength comes in: k8s is declarative, not imperative. You declare that there this pod should be running, and if that's ever not true, Kubernetes will fix it. So, if a pod crashes, Kubernetes will restart it, because that brings the cluster's state back in line with the intended state you declared in the manifest. You can customize this by changing a pod's Restart Policy, but the sensible default of always restarting pods, with an exponential backoff (waiting 10 seconds, then 20, then 40, etc) makes a lot of sense.

This is a really powerful core idea of Kubernetes: you just declare what state you want the cluster to be in, and Kubernetes will make that happen. This way, you spend more time designing a system, and less time manually running commands or pressing buttons to bring your design to life.

Problem: My container should never have downtime, even when it crashes.

Kubernetes restarts Project Kangaroo's backend when it crashes, but those restarts still result in a few seconds of downtime, and even a few seconds is bad. Especially that one time you got a crash loop, because of a really weird edge case, and your service was down for a few minutes. You'd really like the backend to be available, even during crashes and restarts.

The easiest way to do this is with replicas. You just run the same container multiple times, simultaneously -- i.e. you run three replicas -- and that way, if replica 1 crashes, replica 2 and 3 can still serve traffic. Oh, and the system should automatically start a new container, to bring the number of replicas back up to 3. That way the next time a crash happens, you'll have your full array of replicas ready to handle it.

The Kubernetes way to do this is using a Deployment.

# Standard Kubernetes fields for all resources: apiVersion, kind, metadata, spec

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: kangaroo-backend-deployment

labels:

app: kangaroo-backend

# The `spec` is where the Deployment-specific stuff is defined

spec:

replicas: 3

# The `selector` defines which pods will get managed by this deployment.

# We tell Kubernetes to replicate the pod matching the label `app: kangaroo`

selector:

matchLabels:

app: kangaroo

role: backend

# The `template` defines a pod which will get managed by this deployment.

template:

metadata:

# Make sure the pod's labels match the labels the deployment is selecting (see above)

labels:

app: kangaroo

role: backend

# The Pod has its own spec, inside the spec of the Deployment.

# This spec defines what containers the Pod should run.

spec:

containers:

- name: kangaroo-backend

image: kangaroo-backend:1.14.2

ports:

- containerPort: 80

A deployment manages a set of pods. This specific Deployment is managing any Pods with the label app: kangaroo, and it manages them by ensuring there are always 3 replicas of that Pod. We can also nest the definition of the Pod itself inside this Deployment.

If you apply this Kubernetes manifest, you'll see it creates a Deployment. This doesn't explicitly create matching pods, though, so for a brief moment, none of the replicas are running. But remember, Kubernetes is declarative, not imperative. So, Kubernetes notices that its cluster doesn't meet your declared, intended state (3 replicas). So it will take some action to correct that -- i.e. starting a new replica pod. Once that action has been completed, and your pod comes up, Kubernetes will reevaluate the state of the cluster, notice it still has fewer pods that intended, and create a new replica. This repeats until your defined deployment is actually happening.

Problem: My container can't handle the amount of traffic it's receiving.

Project Kangaroo is becoming more popular, and you're getting too much traffic for your backend to handle. You know the solution -- replicas. Replicas can make a service more performant and more resilient! Luckily, you already know how to use Kubernetes Deployments to replicate your container. So you just adjust the Deployment's spec, increasing the number of replicas. Now your service can scale to the amount of traffic.

(There's even elastic scaling, where you can programmatically define some property like "requests per replica per second should be less than 1,000" and let Kubernetes automatically choose necesssary number of replicas. This is called horizontal auto-scaling, and I'm not going to cover it here, but you can read more)

Problem: I need to deploy a new version of my backend, without causing downtime

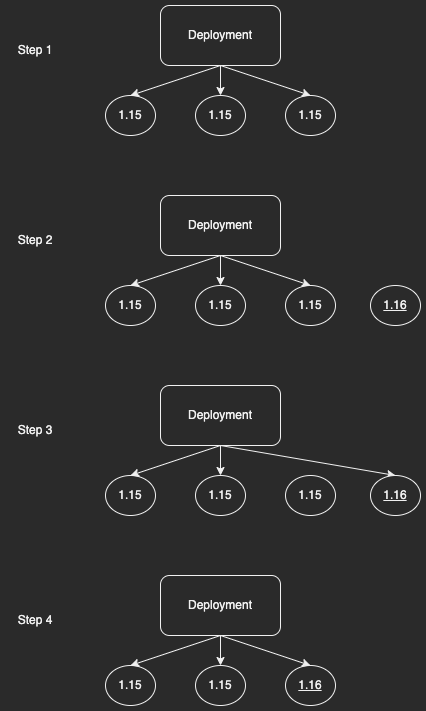

Every week, you release a new version of the Kangaroo backend. The first time you did this, you just deleted the deployment and created a new deployment with a newer version of the kangaroo-backend container. This worked, but it caused a few minutes of downtime, which you're really trying to avoid. How can you update kangaroo version 15 to version 16 without causing downtime?

This is a really common problem, so Kubernetes Deployments already support this. It's called updating a deployment and it's easy. Just edit the deployment and change kangaroo-backend:1.15 to kangaroo-backend:1.16 (either using the kubectl edit CLI, or by editing your YAML manifest, changing the container image, and rerunning kubectl apply). Kubernetes' declarative management kicks in, and notices that the deployment you currently have (on container kangaroo-backend:1.15) is not the same as what you want (kangaroo-backend:1.16). So it will do a rolling upgrade: one at a time, it will

- Notice that the cluster's actual state doesn't match the declared spec (it doesn't have enough replicas on version 1.16)

- Start a new pod on version 1.16

- If that pod starts successfully, Kubernetes will swap it for an old pod in the deployment

- Notice that there's a pod (kangaroo-backend:1.15) that isn't part of any declared spec, so bring the system in line with the declared spec by stopping the pod.

This repeats until all the outdated pods are gone, and only the up-to-date pods remain.

Problem: I need to route traffic to all pods in a deployment

Each pod gets its own Cluster IP address (an IP address that is only meaningful within this Kubernetes cluster -- other clusters, or the wider internet, don't know anything about these IPs). So you can send traffic from the kangaroo frontend to the kangaroo backend using this IP address.

This works just fine until your Pod restarts, or you have a Deployment with multiple Pods, because they'll each have different IP addresses. How do your frontends know which IP addresses they should send kangaroo-backend traffic to? It's time for a new Kubernetes kind called a Service.

# The kangaroo-backend Service.

# Other services inside the Kubernetes cluster will address the

# kangaroo-backend containers using this service.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: kangaroo-backend

labels:

app: kangaroo-backend

spec:

ports:

# Port 8080 of the Service will be forwarded to port 80 of one of the Pods.

- port: 8080

protocol: TCP

targetPort: 80

# Select which pods the service will proxy to

selector:

app: kangaroo

role: backend

Deploying this Service creates a DNS record in your Kubernetes cluster, something like my-svc.my-namespace.svc.cluster-domain.example, or kangaroo-backend.kangaroo-team.svc.mycompany.com. The Service object will monitor which pods match its selectors. Whenever the service gets a TCP packet on its port, it forwards it to the targetPort on some matching pod.

So, now the kangaroo frontend will just send its API requests to that cluster-internal hostname kangaroo-backend.kangaroo-team.svc.mycompany.com, and the cluster's DNS resolver will map it to the kangaroo Service, which will forward it to some available Pod. If you have a Deployment, it'll ensure that you've got enough Pods to handle the traffic. Nice!

Note: both Services and Deployments select pods with a certain set of labels, but they have different responsibilities. Services handle balancing traffic and discovery, Deployments ensure your pods exist in the right number and right configuration. Generally backends/servers I deploy in K8s have 1 Service and 1 Deployment, selecting the same labels.

Problem: Load balancing across Pods

We just went over how a k8s Service lets you address a set of Pods, even when Pods enter or leave that set (e.g. by restarting, or being upgraded). If you were thinking "this sounds like load balancing" then congratulations, you were right!

If you're using a k8s Service to route traffic to your app, then you get basic load balancing3 for free. If a pod goes down, the Service will stop routing traffic to it, and start routing traffic to the other pods with the matching labels (probably pods in the same Deployment). As long as the other pods in the cluster use the Service's DNS hostname, their requests will be routed to an available Pod.

Problem: I want to accept traffic from outside the cluster

So far, your service has accepted traffic from frontends within the cluster, using the Service's hostname. But these cluster IPs and DNS records only make sense in the cluster. This means other services within your company can route to the Kangaroo backend just fine. But how can you accept traffic from outside the cluster, e.g. internet traffic from your customers?

You deploy two kinds of resource: an Ingress and an IngressController.

- An Ingress defines rules for mapping cluster-external HTTP/S traffic to cluster-internal Services. From there, your Service will forward it to a Pod, as discussed above.

- An IngressController executes those rules. Your company has probably already set up an Ingress Controller for your cluster. The Kubernetes project supports and maintains three particular IngressControllers (AWS, GCE and Nginx) but there are other popular ones like Contour, which I use.

Setting up an IngressController is probably the job of a specialized Platform team who maintain your k8s cluster, or by the cloud platform you're using. So we won't cover those. Instead we'll just talk about the Ingress itself, which defines rules for mapping outside traffic into your services.

Note: It's cool that you can define Ingress rules that work abstractly with any particular IngressController, so various projects can offer competing controllers which are all compatible with the same Kubernetes API.

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: Ingress

metadata:

name: minimal-ingress

spec:

ingressClassName: kangaroo

rules:

- http:

paths:

- path: /api

pathType: Prefix

backend:

service:

name: kangaroo-backend

port:

number: 8080

This creates an Ingress, using the default ingress controller for our cluster. The Ingress has one rule, which maps traffic whose path starts with /api to our kangaroo backend. We could define more rules if we want to, for example, map /admin to some admin service. Traffic that doesn't match any rules gets handled by your IngressController's defaults.

Problem: I want to limit networking within the cluster

You take security very seriously on Project Kangaroo. You want to be proactive about security, so you think: what if someone hacked into the kangaroo backend, with a SQL injection or something. You want to contain the damage, and make sure attackers can't pivot their control of the Kangaroo backend to control of other services.

One easy mitigation is to use a Kubernetes Network Policy to limit your project's networking permissions. You use Network Policies to restrict:

- Ingress (who your service can receive traffic from)

- Egress (who your service can send traffic to)

The best security practice is to default deny all networking within your namespace, and then open up specific exceptions for the networking you know your service needs. Here's an example enabling some networking for kangaroo. Note that there are separate rules for ingress and egress. Each ingress rule has two parts:

fromsays which kinds of services can send trafficportssays which ports they can send traffic to

Egress rules have to and ports, configuring which destinations your service can send traffic to, and which ports on those destinations are allowed.

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: NetworkPolicy

metadata:

name: kangaroo-network-policy

labels:

app: kangaroo

role: network-policy

spec:

podSelector:

matchLabels:

app: kangaroo

role: backend

policyTypes:

- Ingress

- Egress

# Each element of `ingress` opens some port of Kangaroo to receive requests from a client.

ingress:

# Anything can ingress to the public API port

- ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 80

# Hypothetical example: say your Platform team has configured cluster-wide metrics,

# you'll need to grant it access to your pod's metrics server. Your company will

# have examples for this. Assume kangaroo-backend serves metrics on TCP :81

- from:

- namespaceSelector:

matchLabels:

project: monitoring-system

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 81

# Each element of `egress` opens some port of Kangaroo to send requests to some server

egress:

# Say the Kangaroo backend calls into a membership microservice.

# You'll need to allow egress to it!

- ports:

- port: 443

to:

- namespaceSelector:

matchLabels:

project: membership

role: api

Problem: I want to use HTTP/S outside the cluster and HTTP inside the cluster

TLS cert management can be a headache -- creating, managing, deploying and regenerating these certs is pretty fiddly, and if something goes wrong, you might accidentally turn off all traffic to your service. So if you've already set up your network policies correctly (see above), you choose to not use TLS within a particular cluster, or namespace. Talk to your team and see if this makes sense for you.

If it does, you probably still want to allow HTTP/S for external traffic -- after all, the internet doesn't have namespaces or respect Kubernetes network policies. So, you'd configure your Ingress to terminate HTTP/S before it sends the requests to your service. This means external customers will do a TLS handshake with your Ingress, and then your Ingress will forward the plaintext HTTP to your service.

Problem: I want to get metrics about my service

You probably want to collect metrics about your service's latency, number of HTTP 200/400/500-class responses, etc. You can instrument your server with something like Prometheus or OpenMetrics or Honeycomb yourself. That works OK, but you'll run into two problems:

- When your service goes down, you can't get metrics from it

- You'll be writing the same metrics in every service you ever deploy. This becomes repetitive and boilerplaty.

Instead, most IngressControllers will collect a bunch of metrics. For example, Contour will monitor every HTTP request that it forwards to your service, and track the latency and the HTTP status. It then exposes these in Prometheus metrics that you can scrape and graph. This is really convenient, because you save time by not implementing these metrics yourself. And when your service goes down, you'll know, because you'll see the Contour metrics for this namespace/service showing spikes in latency or HTTP 5xx responses.

Problem: I want isolation from other projects using the same cluster

Your k8s project has gone well. You shipped the project, everyone loves it. The CTO comes over and asks "how was Kubernetes?" Blinking back tears, you say "not too bad". Your team buys you a mug that says "Best YAML Writer".

Other teams learn from your success and start deploying their projects on Kubernetes. One day they come to you and complain because your Deployment broke their Deployment. Huh? What happened?

It turns out, you wrote a Deployment that matches any pods with the labels role: backend. This works fine when you're the only team working in k8s -- you write a pod template with the label role: backend, and it gets replicated in the Deployment. What if another team deploys a Pod of their own with role: backend? Your Deployment is going to match that Pod, and it'll start replicating another team's stuff! What should you do?

One solution would be to always add a little prefix to those labels, so instead of backend your teams agree to use labels like kangaroo-backend and emu-backend. This relies on everyone having the discipline to keep to the rules. Even if everyone agrees, eventually someone might make a mistake, slip up, and deploy something with the wrong label. This could cause serious problems! Imagine if you accidentally replicated a service that was supposed to be a singleton!

Luckily Kubernetes has a built-in way to isolate teams from each other. It's called a Namespace. They let you isolate teams or projects from each other, so their names don't clash. Just like how multiple types can export methods with the same name, for example, String::new and File::new. Just use --namespace in the kubectl CLI to choose which namespace you want to deploy to.

Note: at Cloudflare, we usually use two namespaces per team, e.g. "datalossprevention-staging" and "datalossprevention-production". Then when we deploy new K8s changes, we can deploy them in staging to make sure they work, and then deploy them in prod, knowing our changes won't interfere with other teams.

Conclusion

Web apps face the same problems, no matter where they're deployed. Managing and load-balancing across replicas, limiting network privileges, zero-downtime upgrades -- none of these are unique to Kubernetes. You might already know how to solve them in your favourite deployment model. Kubernetes provides pretty good out-of-the-box solutions for solving them too, you've just got to translate the standard solutions into Kubernetes jargon (pods, deployments, etc).

To recap:

- A Pod is the minimum unit of deployment. A pod runs one (or more) containers.

- Replicate your pods using Deployments. This gives you:

- Resilience to crashes

- Zero-downtime rolling upgrades

- Scaling to increased traffic

- Load balance across the Pods in your Deployment by using a [Service].

- Limit your Pod's network access with a Network Policy to decrease your vulnerable surface area

- Map external traffic into your pod using an Ingress

- Ingress rules map a particular kind of traffic (protocol, URL, etc) to a particular Service

- Rules are executed by an IngressController. Your cluster admins have probably already set one up

- Isolate teams and projects from each other with Namespaces.

Big thanks to Sana Oshika, Jesse Li, Mingwei Zhang and Rina Sadun for really helpful feedback on drafts of this post. And a very special thank you to Tim and Terin from Cloudflare, who have been so helpful teaching me how to understand and use Kubernetes. They're always answering questions and improving the developer experience. They really exemplify what a great platform team looks like.

Related reading

If you're new to containers, I really liked The Increment's issue all about them. It's got lots of helpful articles.

I really like Ivan Velichko's blog for learning about Kubernetes and docker internals.

Jessie Frazelle's blog is full of really cool container ecosystem bits and pieces, mostly focused on security, but I really liked this piece about running all her desktop apps in Docker.

I bookmarked this article on debugging Kubernetes pods back in 2018 when I was first working with k8s, it was incredibly helpful and I kept referring back to it.

I've also started using k9s, a nice terminal UI for Kubernetes. It's much easier than repeatedly typing kubectl get pods, copy the pod ID, then kubectl describe pod <id>. It's really made exploring my kubernetes projects much easier.

This article by Kris Nóva is about the overlap between systemd and Kubernetes. I'd never thought about their similarities before, but I think she's right -- they're both trying to manage and schedule a lot of services with complex dependency chains. If you squint, Kubernetes is kind of like systemd, except it works across many different machines over a network, and the processes it manages are always in containers. Very thought-provoking article.

Cloudflare has a really interesting Kubernetes setup. We use our own Zero Trust security suite to let programmers access Kubernetes easily, without needing a VPN. This blog post explaining it is worth a read. I actually work on the Zero Trust team, so hearing about pain points/bad UX from the k8s team has helped us improve our product significantly.

Footnotes

Docker is the most popular container engine, but it's not the only one! Containers as a technology predated Docker, but Docker's method for building and running containers was much more user-friendly than its predecessors. For more, I recommend this Increment article

Why is the minimum unit of deployment one or more containers? Why isn't there a way to specify just one container? Why would you want to deploy two containers in the same pod? Well, two reasons. Sometimes your container has a main service (e.g. your API server) and you want to run some auxiliary service too (e.g. to monitor it, or gather metrics/traces). You could do this by running a second service in the same container, but that's not recommended. Instead, you can run the second service in its own container, in the same pod as your main service. k8s people call this the Sidecar pattern. The key is that all the containers in a pod share a network. Each container has their own separate filesystem, mounts, process set, but they share a network. So your containers can address each other and send requests very easily, without any of the need for Network Policies or Services or DNS or load balancing we've seen above. Ivan Velichko has a deep dive on this if you want to learn more.

"Basic load balancing" just means Kubernetes will send traffic approximately uniformly across the available pods. If a pod goes down, traffic will be distributed among the remaining pods. If you want something more complex, you'll need a more complex solution. You might, for example, want a "sticky" load balancer that consistently routes the same host to the same backend pod. Or a load balancer that routes 5% of traffic to a special "canary" pod running the latest release, to check it's healthy before it rolls out widely. Or a smart load balancer that tries to steer traffic towards underutilized pods with more available resources. But again, you'll need to build a specific solution for that. By the time you're worrying about those problems, hopefully you won't need this article :) For more about load balancing, read this.